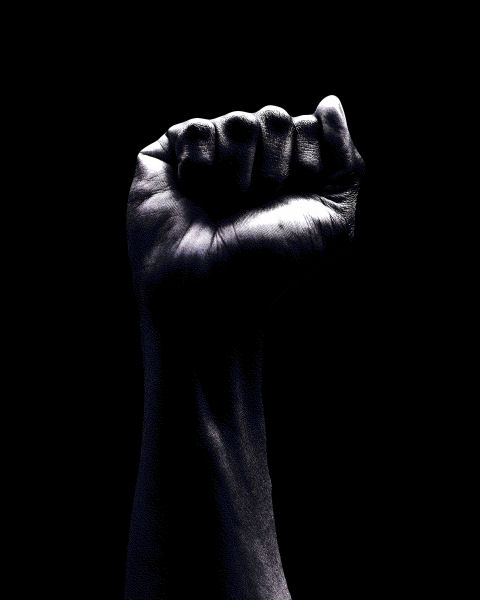

Question Authority

I’ve always been distrustful of authorities.

It’s a common trait of people who were exposed to abuse, neglect or manipulation by parents or teachers. When authority figures satisfy their own needs instead of the needs of the children they are assigned to teach, the children quickly lose trust in authorities. As adults these people often have a “I’ll believe it when I see it attitude”.

I guess that’s why I often check out what authorities have to say about jobs. Well, that, and the fact that what they are saying isn’t anything like what I see in my daily life.

Of course, I’m just one person among a population of more than 350 million. What I’m seeing might be vastly different from the trends or averages of the country as a whole. That’s why I remind myself to be open to the idea that I might be wrong.

If you want to know what’s really happening you need to search for information that might conflict with what you already think. Finding truth is all about seeking and accepting new ideas.

That’s what learning is.

But when I hear Jay Powell, the Fed Chairman, or Kai Ryssdal, the lead reporter at NPRs Marketplace, talk about a robust job market I get suspicious. That’s not what I’m seeing, and it’s not what the numbers from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, (BLS), are telling me either.

It’s as if these guys — authorities we are supposed to trust — aren’t seeing the same things I’m seeing.

I see people I know struggling to make ends meet, wondering how long their job will last and unsure whether they will find another job if they lose the one they have.

The authorities tell us that there are two job openings for every person looking for work. I don’t think so, not in my world.

Instead, I see almost a million people with advanced degrees working part time as adjunct instructors in colleges and universities making only about 25% of traditional professors. About half of the professors in this country are adjuncts. It’s not a tight job market for them. If it were, they’d have a good full time job as a professor.

Or doing something else. That is, if there are two job openings for every job seeker.

Maybe there are…

I see job announcements that list significant barriers to employment. Like entry level positions that require years of experience. Here’s one. Or skill and experience requirements so stringent that it’s clear the employer is looking for someone doing this very same job already.

What’s going on?

One of the great things about being alive at this time in history are the wonderful tools we have to gather information. If you have an internet connection and know where to look, you have access to about everything the PhD s in academia and government have.

Every month the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) releases a report called The Employment Situation. It holds tons of information about the latest trends and changes in the job market.

So, I wonder…

If employers can’t attract applicants, you’d think one of the first things they would do is increase wages. That’s just basic supply and demand. When the supply of something is low — like applicants — the price should rise. That’s been true of just about everything since Adam Smith first saw it happening in 18th century Scotland.

What does the June 2022 Employment Situation say about wages?

“Over the past 12 months, average hourly earnings have increased by 5.1 percent.”

So maybe employers really are trying to attract workers by increasing wages…

But wait a minute…hasn’t inflation been increasing also?

Try this: Type “cpi last 12 months” into your search engine. (CPI stands for Consumer Price Index and measures inflation).

You’ll find this graph at the BLS website:

If inflation is increasing faster than wages the result is the same as employers cutting wages. I thought about this and decided I wanted to see how far behind inflation employers are paying their employees.

In other words, how much labor costs have decreased.

So I went to the same source that Jay Powell uses — the Federal Reserve Economic Database at the St. Lous Fed. It’s open to anyone. Just type FRED into your search engine or the URL window in your browser.

Here with I found (with a little help from Excel):

As you can see, wages outpaced inflation for a few months — that’s when we were giddy about a rare increase in our standard of living — but then started falling behind a few months ago.

Inflation has increased by about 8% while wages have increased about 5% during the same period. For workers, that’s an effective pay cut of around 3%. For employers, it’s a labor cost savings of 3%.

Employers would have to increase wages by more than 3% to attract workers, but there is no way we’ll ever see that. That’s why you feel like you are getting poorer.

You are.

But there’s more…

Employers might be crying for applicants, but they aren’t hiring. Here’s an interesting tidbit from the June Employment situation:

“The number of persons not in the labor force who currently want a job was essentially unchanged at 5.7 million in June. This measure is above its February 2020 level of 5.0 million. These individuals were not counted as unemployed because they were not actively looking for work during the 4 weeks preceding the survey or were unavailable to take a job.”

There are several interesting things in this paragraph…

First, there are 5.7 million unemployed people who want a job, but they are not being counted as unemployed because they didn’t actually look for work in the past month. Some of them are probably caring for sick or ill family members. Maybe they are sick or injured themselves. Others might have lost their car and can’t get to work until they can buy another. Their unemployment benefits might have run out and they are frantically looking for food and shelter.

These people can work if the job is right, and they want to work. How come employers aren’t hiring them? Many can probably work from home via the internet.

Next, this number is increasing.

There are 700,000 more people in this situation than there were 27 months ago. Three quarters of a million more people who can’t look for a job because of some kind of hardship. And remember, they are not receiving unemployment benefits. When benefits run out you are no longer counted as unemployed.

You are out of the labor force.

This is something authorities like Jay Powell doesn’t talk about and media mavens like Kai Ryssdal rarely ask them about.

What is Out of the Labor Force?

The BLS defines it as:

“This measure is the number of people in the labor force as a percentage of the civilian noninstitutional population 16 years old and over. In other words, it is the percentage of the population that is either working or actively seeking work.”

It is measured with the Labor Force Participation Rate:

Click here to see the graph more clearly at its FRED home.

The Labor Force Participation Rate began a steady increase beginning in 1965. There were jobs for more and more people as they entered the labor force.

Until 2001.

Then the Labor Force Participation Rate began to steadily decline. Of course the population kept rising.

Soon there simply were not enough jobs to go around.

Here’s what this looks like in a graph:

It’s clear that the number of jobs have not kept up with the demand for them.

By the way…

For the last five years population growth has averaged 1.824 million a year. That’s 152,000 a month.

Think about that the next time you hear that “we’re gained back all the jobs” since the last recession or pandemic. It’s nothing to celebrate.

Is anything said about the 152,000 new entrants into the job market every month? How about the latest 1.824 million people each year looking for a job?

Probably not.

One last thought…

Taking responsibility for our knowledge takes power out of the hands of people with agendas and biases and puts it where it belongs — with us. It’s an important part of democracy because it keeps our political representatives and their underlings honest and forthright. But in order for that to happen we not only need to know what is happening, but also to confront the authorities with what we have learned.

That’s why I’m sending a link to this article to Jay Powell and Kai Ryssdal.

Read more at VicNapier.com and my Medium.com page.

Like What You’ve Read? Become a Medium.com Member!

Links may lead to sites where the author has an affiliate relationship